by Paige Vinten Taylor

Poetry invites experimentation. Many writers have accepted the invitation and found ways to uniquely express themselves—by diverging from traditional formats in ways that enhance the meaning and imagery of their poems. We’ll take a look at a few of these artists and excerpts from their work, with a particular eye for the verse they created for children.

E. E. Cummings (1894–1962) left a major mark on the genre of poetry. Poet-critic Randall Jarrell said of him, “No one else has ever made avant-garde, experimental poems so attractive to the general and the special reader.”1 Cummings rarely capitalized words (his name, included) and used space and punctuation in unusual ways, jarring readers from the expected and getting them to think about the words and their meanings in the context of the poems.

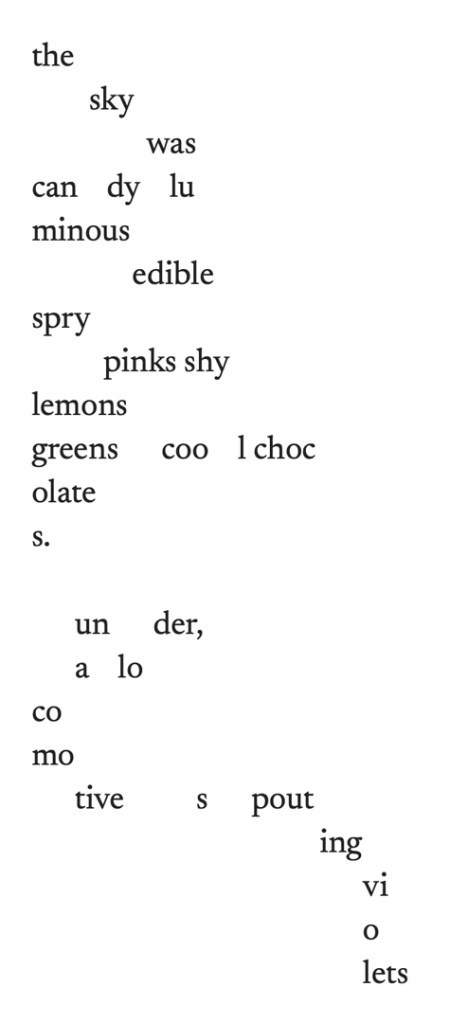

In his song-poem “the sky was,”2 printed below, he not only places extra space between words, but also between parts of words, while running fragments of other words together. Notice, too, the lack of capital letters, as well the missing period at the end of the poem. Further, as an artistic touch, he shapes the second half of the poem as if it were coming out of the smokestack of a locomotive, alluding to the poem.

In other work, Cummings often scattered punctuation in unexpected places and positioned words out of order for unconventional syntax. His radical departure from the norm encouraged creative formatting among poets who followed him.

British poet and artist Edward Lear (1812–1888) wrote hundreds of poems. His classic “The Owl and the Pussycat”3 has long been one of the first poems children learn. This lyrical poem has an unusual format: Each of its three stanzas has eleven lines. That odd number of lines is odd formatting to begin with. Then, each stanza concludes with a song-like pattern—but with different words in each “chorus.” This deliberate break from convention matches the playful nonsense of the poem’s narrative and allows Lear to carry the reader along on an unexpected journey. Below is his finish:

Dear Pig, are you willing to sell for one shilling

Your ring?’ Said the Piggy, ‘I will.’

So they took it away, and were married next day

By the Turkey who lives on the hill.

They dined on mince, and slices of quince,

Which they ate with a runcible spoon;

And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,

They danced by the light of the moon,

The moon,

The moon,

They danced by the light of the moon.

What could be more delightful? No wonder the poem was voted by the British public as their favorite childhood poem.4

In addition to penning the Winnie the Pooh series, A. A. Milne (1882–1956) wrote a number of poems, included in his collections Now We Are Six and When We Were Very Young. The latter contains his well-known verse “Halfway Down,”5 presumably spoken by Christopher Robin. Breaking up the poem into short lines gives its words and phrases their own emphases. Further, it gives the rhyme a boost: In the phrase “quite like it” we would normally put the stress on the word “like.” However, placing “it” on a separate line slows us down a bit as we read, and gives that word more stress—allowing the rhyme with “sit” to be better heard. Here is the first half of the poem:

Halfway down the stairs

is a stair

where i sit.

there isn’t any

other stair

quite like

it.

i’m not at the bottom,

i’m not at the top;

so this is the stair

where

I always

stop.

Formatting in this way also helps to bring out Christopher Robin’s characteristic way of speaking and gives a glimpse of his lovable personality.

And, of course, no discussion of poetic structure would be complete without including concrete poems, in which words and graphics are united. The late Myra Cohn Livingston, active for many years in SCBWI as a poet, author, and teacher, described concrete poems as “playing with words, ideas, letters and art, [and giving] delight to the eye”—so appealing to children as well as adults. Her book Poem-Making: Ways to Begin Writing Poetry includes examples from a number of inventive poets.6

Also, we see extraordinary concrete poems in contemporary poet Joan Bransfield Graham’s Awesome Earth: Concrete Poems Celebrate Caves, Canyons, and Other Fascinating Landforms.7 Bransfield, who was recently interviewed in Kite Tales, cleverly integrates her poetry with the various landforms she features. For example, she intersperses her vivid descriptions vertically in the gaps among stalagmites and stalactites, accentuating their elongated, pointed shapes. Her book is a lovely tribute to the earth and concrete poems.

These artists—and many others—have shown that making changes to traditional formats allows them to convey the meaning and/or emotion of their poems more effectively, while often adding creative touches and vitality to them as well.

Whether you are reading poetry for your own pleasure or sharing its beauty with a child, I hope these musings help you enjoy the play of form even more during this National Poetry Month.

For more fantastic content, community, events, and other professional development opportunities, become a member today! Not sure if there is a chapter in your area? Check here.

Paige Vinten Taylor is a longtime member of SCBWI. She has poems and short stories published in a variety of magazine and journals, including Highlights for Children, Turtle, The Saturday Evening Post, and Light: A Journal of Light Verse.

Notes

- “E. E. Cummings 101,” Poetry Foundation, originally published August 16, 2016, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/90442/ee-cummings-101. ↩︎

- E. E. Cummings, “The Sky Was,” in XLI Poems (Dial Press, 1925), https://cummings.ee/book/xli-poems/. ↩︎

- “A Short Analysis of Edward Lear’s ‘The Owl and the Pussycat,'” Interesting Literature, originally published December 2016, https://interestingliterature.com/2016/12/a-short-analysis-of-edward-lears-the-owl-and-the-pussycat/. ↩︎

- “A Short Analysis of Edward Lear’s ‘The Owl and the Pussycat.'” ↩︎

- A. A. Milne, “Halfway Down,” in When We Were Very Young (H.P. Dutton, 1924), https://allpoetry.com/Halfway-Down. ↩︎

- Myra Cohn Livingston, “Concrete, Shape, and Pattern Poetry,” in Poem-making: Ways to begin Writing Poetry (A Charlotte Zolotow Book, 1991). ↩︎

- Joan Bransfield Graham, Awesome Earth: Concrete Poems Celebrate Caves, Canyons, and Other Fascinating Landforms (HarperCollins, 2025). ↩︎